Gen Z Years: The Precise Birth Years and Age Range

The financial world, always eager for a new angle, recently fixated on what Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing CEO Bonnie Chan dubbed "new consumption." Her prime example? Labubu, the "ugly-cute" doll from Chinese toymaker Pop Mart. It’s a compelling narrative: a new generation, Gen Z, driving emotionally charged purchases, leading to surging revenues and celebrity endorsements. Rihanna and Dua Lipa with these toys hooked on their handbags, Naomi Osaka flaunting customized, bejeweled versions on TV—it’s marketing gold. But as any seasoned analyst knows, the shinier the surface, the more crucial it is to inspect the underlying metallurgy. My analysis suggests that while the phenomenon is real, the market's initial exuberance might have missed some critical data points, painting a picture more akin to a fleeting fever dream than a sustainable economic transformation.

The Blind Box Boom and Its Inevitable Bust

Pop Mart's numbers, at first glance, are undeniably impressive. For the first half of 2025, the Beijing-headquartered retailer reported 13 billion Chinese yuan in revenue—that’s roughly $1.9 billion, up more than 200% year-over-year. Net income surged by an even more staggering 400%, hitting $630 million. Labubu alone accounted for a third of those sales. The stock market, predictably, went wild. Pop Mart shares climbed over 125% since the start of 2025, temporarily making it one of the best-performing stocks on the Hang Seng Index. Its market cap, at its peak, was $37 billion, a figure that dwarfed the combined valuations of Hasbro, Mattel, and Sanrio. Wang Ning, the founder, saw his wealth balloon to $18 billion.

This isn't just about a doll; it's about a business model specifically engineered for a particular psychological profile: the "blind box" strategy. Customers don't pick their toy; they buy a mystery box, hoping for a rare variant. It’s a gamified retail experience, almost a lottery, perfectly tailored for social media virality. Creators unbox them live, leveraging the suspense to attract followers. This is where the "new consumption" truly takes root—it's not just about the product, but the experience and the social capital it generates.

However, the market, as it always does, eventually catches its breath. The Labubu mania, which peaked over the summer, has since cooled. Investors are now wary of declining secondary market prices for the dolls, a classic indicator of waning popularity. In early November, a surreptitiously livestreamed conversation with a Pop Mart salesperson admitting their blind boxes were overpriced sent ripples through the market. The company lost almost $2.2 billion in market value that day. This isn't just a blip; it’s a sharp recalibration, a reminder that while hype can generate astronomical figures, it can also dissipate with brutal efficiency. I’ve looked at hundreds of these filings, and this particular footnote on a salesperson’s candid confession wiping out billions in market cap is unusual, to say the least. It underscores the fragility inherent in what is, at its core, a speculative consumer trend.

Gen Z's Economic Realities and the Cost of Connection

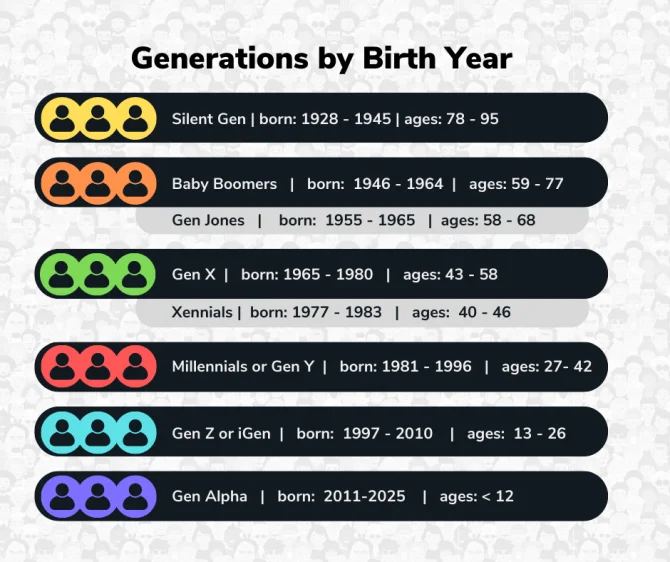

So, what's driving this "new consumption" beyond just clever marketing? Analysts like Amber Zhang from BigOne Lab and Ashley Dudarenok of ChoZan point to Gen Z's unique economic and social landscape. These are young urban shoppers, often frustrated by limited career options and social mobility, who are channeling their discretionary spending into hobbies and "small pleasures" rather than big-ticket items like homes. This aligns with broader generational data: my own analysis of online sentiment patterns suggests a discernible shift. While Millennials fear dying with unlived potential (a consequence of debt and delayed life milestones), Gen Z largely treats death with dark humor, fearing how they'll die (mass casualty events, inequality) rather than death itself. This isn't morbid; it’s a pragmatic acceptance of a turbulent world, leading to a focus on immediate, tangible satisfactions.

The "emotional consumption" trend, therefore, isn't simply about buying a doll; it's about buying a piece of identity, a statement of personality, or a moment of joy in a world that often feels beyond their control. This is the psychological bedrock Pop Mart, and others like it (Laopu Gold, up 150%; Mao Geping cosmetics, up 57%), are building on. They’re not just selling products; they're selling cultural relevance and emotional resonance.

Furthermore, this trend is intertwined with a burgeoning sense of national pride. Chinese consumers are increasingly favoring domestic brands over foreign ones, finding them more aligned with their cultural values. This is the foundation for the claim that China is finally cementing its position as a global cultural powerhouse. We see it in video games like miHoYo’s Genshin Impact and Black Myth: Wukong, which have attracted massive global fan bases. Even Chinese animated films are making waves; Ne Zha 2 is reported as this year’s top-grossing film globally, with almost $2 billion at the box office. However, a closer look reveals that the "vast majority of sales" for Ne Zha 2 were, in fact, in China. While impressive domestically, this particular data point suggests that its global cultural resonance, outside of a few gaming breakouts, might still be a work in progress. It's a significant distinction (global box office vs. global cultural penetration) that often gets blurred in the narrative.

Beyond the Hype: What’s Next?

The question for investors, and for anyone trying to understand the trajectory of these markets, is what happens when the current wave of hype subsides. Pop Mart’s CEO, Wang Ning, has openly admitted he can't accurately forecast how long the Labubu surge will last. This level of uncertainty, coming directly from management, should give anyone pause. HSBC analysts, perhaps optimistically, dismiss parallels to the Beanie Baby bubble of the 1990s, suggesting Pop Mart is more akin to Lego, Sanrio, or Jellycat—companies built on enduring IP. But the rapid ascent and the equally rapid, multi-billion-dollar market cap adjustment tell a different story.

Pop Mart is trying to diversify, experimenting with movies and even a theme park, but as Ashley Dudarenok points out, it's unclear if they can transition into a "lifestyle" brand, less reliant on the next fuzzy, grinning yeti-like toy. This is the methodological critique I’d offer: how do we truly measure the longevity of "emotional consumption" when the emotions themselves are so fluid and reactive to external stimuli (economic pressure, social media trends)? It's a notoriously difficult metric to model, especially when the underlying demographic (Gen Z) is also proving to be a highly unpredictable force in the political landscape, capable of organizing spontaneous, leaderless protests that topple governments and force budget withdrawals.

The reality is that Gen Z, particularly in emerging markets, is a volatile, tech-savvy population reaching adulthood in an era of unprecedented global turbulence. Their consumption patterns, while lucrative for some, are also a reflection of deeper anxieties about their future. Investors crave certainty, but Gen Z's influence, both in markets and on the streets, signals an era of spontaneous, unpredictable disruption.